Home

Royal Navy Instructor Officers

How Meteorology became part of

the Royal Navy

Origins | History | Development | World War 2 | D-Day Weather | D-Day Personalities

OriginsSince pre-historic periods men and women have looked to the sky and wondered what the weather was going to do- perhaps for planned hunting trip or drying pelts gathered from such a trip. Originally it was assumed that the sun ruled the earth’s weather and it was therefore worshipped as a god. Of course in many ways, arguably, we now know that premise to be more or less correct. It is worth remembering that during much of the Bronze Age period climatic conditions in the UK and Europe as a whole were much warmer than those we currently experience, allowing expansion and exploration northwards, although this trend was reversed during much of the cooler Iron Age period. As soon as mankind adopted an agrarian lifestyle however, having some understanding of the patterns of the weather became essential for crop cultivation. If the crops failed because of drought or flooding, then the villagers would starve. In fact we know that as early as about 650 BC, the Babylonians under stood enough about the skies to attempt to forecast short-term weather changes based on the appearance of clouds and other optical phenomena such as haloes. One of the earliest Greek scholars, Aristotle (384-322BC), discussed and lectured to his students on the physical dynamics of some of the elements that made up the weather, publishing the treatise ‘Meteorologica’; setting the stage for a study of the subject using empiric scientific methodology. Whilst he made some acute observations, he also made some significant errors; nevertheless the text was considered an authority on weather theory for nearly two millennia, well into the 17th century. For most however, interest in the weather was still mainly grounded in religion; not only was the sun worshipped; the winds were also believed to have divine powers. Some of the earliest meteorological measurements, as we understand the term, would have been those of the wind direction. We know, for example, that in Greece and pre-Christian Rome, weather vanes were erected on the villas of wealthy citizens, depicting gods such as Boreas (god of the north wind), Aeolus (custodian of the four winds), Hermes and Mercury. In fact the earliest recorded weather vane (built around 48 BC) sat on the ‘Tower of the Winds’ in Athens and honoured another Greek god, Triton, god of the sea. The Roman period, during the early years of the 1st century BC, was a particularly benign and settled time, allowing construction on upland sites across Europe and the UK; the south of Britain even became self sufficient in wine production with large vineyards in the south east of Britain an essential staple of life in late Roman times. In general though the climate became much less settled from the 1st century AD onwards. There is evidence of notable flooding, with 10,000 people drowning, along the East Coast and Thames Estuary around AD48. From about that period we have better evidence of the disasters which occurred as a result of weather fluctuations, as people began to recognise the importance of documenting such events, perhaps to see if there was a pattern in their occurrence. With further exploration and regular trading links, the necessity to have some understanding of the likely wind and weather patterns for longer sea voyages and exploration cannot be understated. Archaeologists have discovered bronze Viking weather vanes from the 9th century with an unusual quadrant shape, usually surmounted by an animal or creature from Norse fable. Such vanes can be seen even today in Scandinavia. Weather vanes have a history of depicting various figures, especially animals thought relevant to the weather. Perhaps the most famous symbol associated with the vane is the cockerel. In the ninth century the pope reportedly decreed that every church in Europe should show a cock on its dome or steeple, as a reminder of Jesus’ prophecy that the cock would not crow the morning after the Last Supper. As a result “weather cocks” have topped church steeples for centuries. We know that the Normans understood the significance of the weather patterns for in 1066, west-north westerly winds prevailed in the Channel all through summer and into September. According to the climatologist Lamb, it was only the breaking of this spell that gave William of Normandy his chance to cross the Channel on the 7th October 1066 to invade England, landing, close to the site of our own shop, at Pevensey, to defeat King Harold II. The Bayeux Tapestry completed by his decree by his half brother, Bishop Odo, by around 1077, includes a scene of a craftsman attaching a wind vane to the spire of Westminster Abbey. The 13th century saw what has become known as the ‘little ice age’, a period when glaciers advanced across Europe and there were some exceptionally severe winters recorded. For example the winter of 1407-1408 which affected most of Europe, is regarded by climatologists as one of the most severe on record. Ice in the Baltic allowed traffic between the Scandinavian nations, with wolves moving across frozen pack ice from Norway to Denmark. However despite the clear impact of such events there was little understanding of the nature of the reasons behind them and consequently no ability to forecast how long they might last or linger. People tended to believe that by noting the effect of the weather on nature, especially flora and fauna they might deduce what the future might hold. Such forecasting as there was, was generally confined to ‘weather lore’, examples of which still survive today. To some extent there is a degree of accuracy in some of these sayings, as seaweed, pine cones, and animal behaviour are undoubtedly affected by the extent of moisture change in the environment and pressure rises and falls. The later period of the Italian Renaissance in the 15th century should perhaps be seen as the birth of what we might regard as the modern era of weather forecasting. By then it was recognised that much of what was understood about the workings of the atmosphere was simply insufficient, especially as the desire to better forecast the weather experienced on the great exploratory sea voyages of the period manifested itself. English philosophers such as Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626) led the revolution in scientific thinking by developing the theory of ‘observation and experimentation’ –the way in which all credible meteorological (and other scientific) research and discovery has been conducted ever since. In order to conduct research on this manner better instruments were needed, to measure the fundamental properties of the atmosphere; its moisture, temperature, and its pressure. The first hygrometer (to measure the humidity of the air), had already been invented by the German, Nicholas Cusa as early as the mid-fifteenth century. By 1592, the Italian, Galileo Galilei had invented an early thermometer and the Italian, Evangelista Torricelli invented an instrument he called the barometer, for measuring atmospheric pressure, in 1643. Alongside these, using the principles developed by Bacon and others, came a better understanding of the physical properties of the environment. Robert Boyle (1627-1691), an Irish physicist and chemist and co-founder of the Royal Society discovered that when the temperature is held constant, the volume of a gas is inversely proportional to its pressure- when the pressure increases, the volume decreases and visa versa. Such ideas helped offer a better understanding on the nature of the motion and flow of fluids in motion around and through the earth’s atmosphere. As these ideas were published, the equipment to measure the parameters they discussed, in a standardised form, became available for the first time by about the mid 17th century. Mariners were then able to take then on board ships and make regular comparisions of the variables as they covered vast distances, and more importantly for us, keep records of such measurements. Marine weather logbooks from merchant and Royal Navy ships still offer a wealth of valuable information about weather conditions at various times across the globe. By the mid 18th century a fashion for keeping such records became popular with the gentlemen of the day; especially those who were able to lead a leisurely lifestyle such as members of the clergy and nobility. We have some examples of some earliest diaries being written solely to record the weather. Examples of diaries made in Rye (E Sussex) from 1730-3, Exeter from 1755-75 and Stroud from 1771-1813 are held in the National Meteorological archives in Exeter. These coincided with the publication of a wide range of scientific papers specifically investigating the physical mechanics of the atmosphere and its related patterns. By about the same time as large quantities of recorded data were becoming available it was recognised that there was a need for a kind of index or classification of the way in which the physical properties of the atmosphere manifested themselves. Jean Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) proposed a list of descriptive terms in French but it was Luke Howard, who became known as the ‘godfather of clouds’ who devised three principal categories: cumulus, stratus and cirrus, as well as a series of intermediate and compound modifications to accommodate the transitions occurring between the forms. His elegant definitions are still in use today.

The development of observational networks for the purpose of regular collection of data helped forecast the weather. A leap forward was taken though with the introduction of numerical weather forecasting, that is the prediction of the weather by solving numerous mathematical equations related to the laws of interaction between hydro and thermo dynamics.A lot of work was carried out in this field by the Norwegian Vilhelm Bjerknes in 1904 but it was only fully developed by a British mathematician named Lewis Fry. The Bergen School of Bjerknes also suggested in the early 1920’s that significant processes occurred in narrow zones between them; they named these areas ‘fronts’ (from the term ‘battle fronts’ used in the First World War) and developed our classic interpretations of models of low pressure. However, it wasn’t until the early 1920’s that perhaps the most important part of the jigsaw became available, namely accurate data from above the surface. Although weather balloons had provided temperature and wind data at a few thousand feet taken from occasional manned forays since the 18th century, forecasting lacked any real understanding of the dynamics of the processes occurring at upper levels that were clearly the major controlling factor in determining changes in the day to day weather patterns. The development of radio-sondes in the 1920’s (lightweight boxes equipped with weather instruments and a radio transmitter carried into the upper atmosphere by a hydrogen or helium-filled balloon) helped prove the theoretical characteristics of warm, cold and occluded fronts. In fact it was both the two world wars that made clear the strategic importance of a better understanding of the weather and more money and resources were made available as a result. During the Second World War for example, RADAR (Radio Detection and Ranging) was developed and then used for weather forecasting. It enabled scientists to more accurately track weather balloons as well giving better information about the direction of cloud travel. It took the development of powerful computers, that were fast enough to complete the vast number of calculations required to produce a forecast before the event had occurred in the late 1960’s to offer us accurate forecasts out to 4-5 days ahead that we now take for granted. A modern day weather forecasting system consists of five components: data collection, data assimilation, numerical weather prediction, model output post processing- and finally- a presentation of the forecast to the user, through the most useful medium, be that press, tv, radio or other medium. Nevertheless, despite all this, there are still many people that look up at the sky every day, much as the ancients did, and wonder what the weather will be doing tomorrow. Source: https://www.weathershop.co.uk/blog/history-of-the-weather/ |

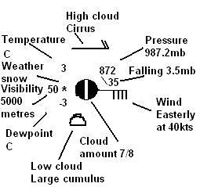

By the early-mid nineteenth century the invention of

the telegraph and the emergence of telegraph networks, allowed the routine

transmission of weather observations to and from observers and compilers. As

data become available in near real time across at least some parts of the globe

it Synoptic became possible to draw crude weather maps identifying the weather

conditions at the same place and time across relatively large areas, such as

the UK. From this it became clearer that it was possible to identify surface

wind patterns and complete storm systems. The success of the early weather maps

with the public as well as their scientific credulity, spawned a desire to

create a network of weather observing stations. This eventually gave birth to

the type of forecasting used right into the latter part of the last century,

synoptic weather forecasting, based on the compilation and analysis of many

observations taken simultaneously over a wide area. Working charts were

prepared by the newly designated ‘Meteorological Office’ from 1861.

The UKMO library now holds weather reports for the UK and the world for every

day from the 1st January 1869 to the present.

By the early-mid nineteenth century the invention of

the telegraph and the emergence of telegraph networks, allowed the routine

transmission of weather observations to and from observers and compilers. As

data become available in near real time across at least some parts of the globe

it Synoptic became possible to draw crude weather maps identifying the weather

conditions at the same place and time across relatively large areas, such as

the UK. From this it became clearer that it was possible to identify surface

wind patterns and complete storm systems. The success of the early weather maps

with the public as well as their scientific credulity, spawned a desire to

create a network of weather observing stations. This eventually gave birth to

the type of forecasting used right into the latter part of the last century,

synoptic weather forecasting, based on the compilation and analysis of many

observations taken simultaneously over a wide area. Working charts were

prepared by the newly designated ‘Meteorological Office’ from 1861.

The UKMO library now holds weather reports for the UK and the world for every

day from the 1st January 1869 to the present.